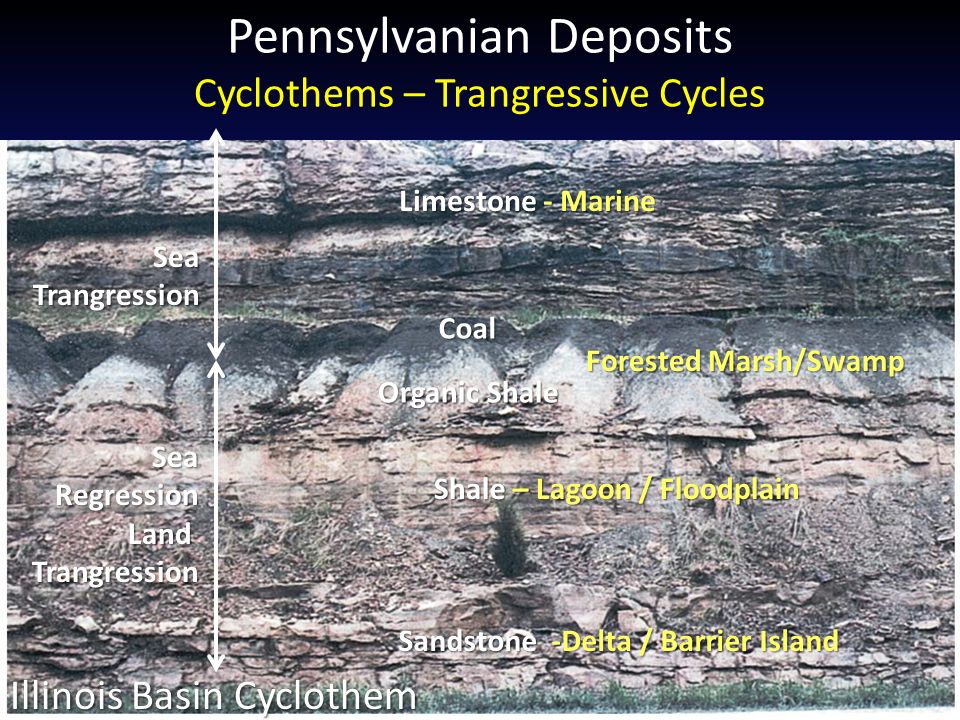

Cyclothems- Cyclothems are alternating stratigraphic sequences of marine and non-marine sediments, sometimes interbedded with coal seams that are indicative of cyclic depositional regimes. The cyclothems consist of repeated sequences, each typically several meters thick, of sandstone resting upon an erosional surface, passing upwards to pelites (finer-grained than sandstone) and topped by coal.

Mélange- A mélange is a large-scale breccia, a mappable body of rock characterized by a lack of continuous bedding and the inclusion of fragments of rock of all sizes, contained in a fine-grained deformed matrix(typically shale, slate, or serpentinite, with a tectonic fabric). The mélange typically consists of a jumble of large blocks of varied lithologies. Both tectonic and sedimentary processes can form mélange.

Mélange occurrences are associated with thrust faulted terranes in orogenic belts. A mélange is formed in the accretionary wedge above a subduction zone. The ultramafic ophiolite sequences which have been obducted onto continental crust are typically underlain by a mélange. Smaller-scale localized mélanges may also occur in shear or fault zones, where coherent rock has been disrupted and mixed by shearing forces.

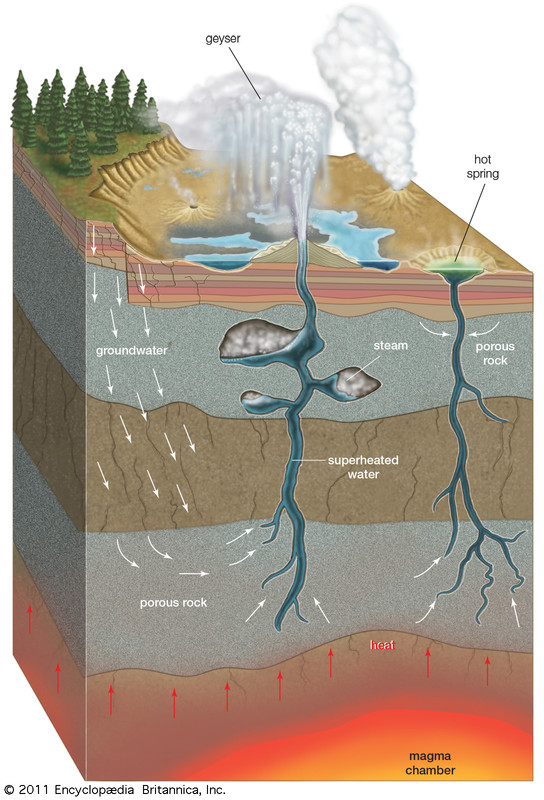

Fumarole, vent in the Earth’s surface from which steam and volcanic gases are emitted. The major source of the water vapour emitted by fumaroles is groundwater heated by bodies of magma lying relatively close to the surface. Carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, and hydrogen sulfide are usually emitted directly from the magma. Fumaroles are often present on active volcanoes during periods of relative quiet between eruptions.

Fumaroles are closely related to hot springs and geysers. In areas where the water table rises near the surface, fumaroles can become hot springs. A fumarole rich in sulfur gases is called a solfatara; a fumarole rich in carbon dioxide is called a mofette.

Geyser, hot spring that intermittently spouts jets of steam and hot water. Geysers result from the heating of groundwater by shallow bodies of magma. They are generally associated with areas that have seen past volcanic activity. The spouting action is caused by the sudden release of pressure that has been confining near-boiling water in deep, narrow conduits beneath a geyser. As steam or gas bubbles begin to form in the conduit, hot water spills from the vent of the geyser, and the pressure is lowered on the water column below. Water at depth then exceeds its boiling point and flashes into steam, forcing more water from the conduit and lowering the pressure further. This chain reaction continues until the geyser exhausts its supply of boiling water.

As water is ejected from geysers and is cooled, dissolved silica is precipitated in mounds on the surface. This material is known as sinter.

Mud volcano, mound of mud heaved up through overlying sediments. The craters are usually shallow and may intermittently erupt mud. These eruptions continuously rebuild the cones, which are eroded relatively easily.

Some mud volcanoes are created by hot-spring activity where large amounts of gas and small amounts of water react chemically with the surrounding rocks and form a boiling mud.

Variations are the porridge pot (a basin of boiling mud that erodes chunks of the surrounding rock) and the paint pot (a basin of boiling mud that is tinted yellow, green, or blue by minerals from the surrounding rocks). Other mud volcanoes, entirely of a nonigneous origin, occur only in oil-field regions that are relatively young and have soft, unconsolidated formations. Under compactional stress, methane and related hydrocarbon gases mixed with mud force their way upward and burst through to the surface, spewing mud into a conelike shape. Because of the compactional stress and the depth from which the mixture comes, the mud is often hot and may have an accompanying steam cloud.

Hot spring, also called thermal spring, spring with water at temperatures substantially higher than the air temperature of the surrounding region. Most hot springs discharge groundwater that is heated by shallow intrusions of magma (molten rock) in volcanic areas. Some thermal springs, however, are not related to volcanic activity. In such cases, the water is heated by convective circulation: groundwater percolating downward reaches depths of a kilometre or more where the temperature of rocks is high because of the normal temperature gradient of the Earth’s crust—about 30 °C (54 °F) per kilometre in the first 10 km (6 miles).